Light's Powerful Impact on Sleep: Managing Exposure for Better Rest

Often overlooked, light exposure acts as the primary cue that synchronizes your body's internal clock, impacting when you feel sleepy or alert.

👋 Welcome to this edition of Sleepletter™ where we offer you easy-to-read insights from the latest research papers from the field of sleep neurobiology and clinical sleep medicine. Sign up to also receive Sleepletter by email.

Did you know that light is the single most important cue for our circadian rhythm, i.e. the internal 24h rhythm that controls our sleep and wake? Yes, light indeed holds a powerful influence over our sleep-wake rhythms and sleep quality. Our bodies rely on light cues to synchronize the circadian master clock in our hypothalamus guiding our 24-hour sleep/wake cycles. Other than light, several other so called “zeitgebers (English: time-cue)” such as meal times, temperature and exercise coordinate our sleep and wake. Since light is the most important one, let’s dig deep and why it’s so important for our sleep.

The master circadian clock “ticks” inside the brain's hypothalamus, regulating numerous physiological processes over roughly 24 hours through neuronal and hormonal signaling. This innate timer controls the timing of sleep and wakefulness. The clock synchronizes to environmental light/darkness via input from the eye's retina. More specifically, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (IPRGCs) in the retina send signals via the optic nerve to the hypothalamus to “inform” our circadian clock whether it’s light or dark in the environment. Then, the clock “decides” whether it’s day or night outside based on, but not solely, these signals.

Daylight keeps the circadian clock properly aligned so we feel alert and awake during daytime hours. As daylight wanes and evening approaches, the brain’s pineal gland ramps up production of the hormone melatonin which induces drowsiness and facilitates sleep. Light exposure at night, especially blue wavelengths emitted from electronic screens (e.g from your phone or tablet), suppresses melatonin release rapidly, thereby disrupting the normal circadian rhythm. Furthermore, insufficient daylight exposure during daytime hours also impairs robust melatonin release come nightfall.

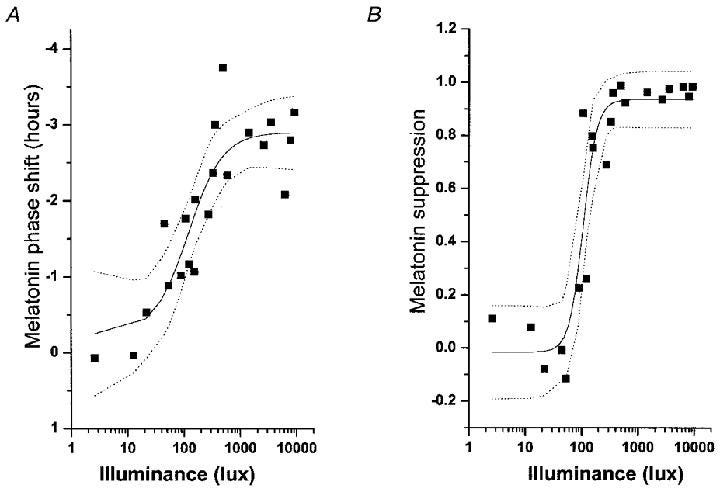

Too much or too little light exposure plays havoc with multiple aspects of sleep. Light pollution from excessive outdoor lighting as well as pervasive artificial lighting indoors during nighttime disturbs circadian rhythms. Night shift workers suffer chronically disrupted circadian cycles because they work in brightly lit environments at night, but then try to sleep during daylight hours. Even the semi-annual changing of clocks between standard and daylight savings time nudges circadian clocks out of sync with the 24-hour solar day. It may come as a shock just how drastically artificial light exposure at night suppresses our natural melatonin production. Studies show that exposure to room light (<200 lux) in the evening can suppress melatonin by over 50%. Even a brief pulse of brighter light at night curtails melatonin synthesis — one study found that 30 minutes of exposure to ordinary room light at night suppressed melatonin by nearly 90% (See Figure 1 below). With over 99% of Americans and Europeans exposed to artificially illuminated skies that can disrupt the circadian rhythm, it's no wonder so many struggle with poor sleep quality. This pervasive nighttime light pollution throws our innate circadian timekeeper out of sync, reduces sleep-promoting melatonin, and can have detrimental health effects in the long term.

Fortunately, we can leverage light therapeutically to optimize our sleep. Since light anchors the circadian clock, maximizing light exposure earlier in the day can be very beneficial. Being exposed to bright light first thing in the morning, say by opening all blinds, eating breakfast next to a window, or taking a morning walk outdoors, anchors the circadian clock properly to the 24-hour cycle. In contrast, we must diligently manage exposure to blue light wavelengths after sundown. Avoiding electronic screens in the 1-2 hours before bedtime, using blue light filters on devices, and reading paper books instead of tablets permits our natural nightly rise in melatonin, facilitating sleep. Keeping bedrooms as dark as possible at night using blackout curtains or sleep masks limits light disruption of melatonin secretion. For those with circadian rhythm disorders, supplemental light therapies like dawn simulators, light therapy lamps, and blue-wavelength blocking glasses can help stabilize dysregulated cycles. Of course, making sleep a consistent priority by establishing a regular bedtime routine in dim lighting encourages robust circadian entrainment and healthy sleep.

While the demands of modern life frequently disrupting our natural circadian rhythm, understanding the science behind light's influence on sleep is an important first step in managing light exposure. So next time you go to bed, make sure to turn off those pesky lights, close the blinds and let you body enjoy the night sleep to be in the best possible shape for tomorrow's victories.

***

About the author

Alen Juginović is a medical doctor and postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School studying the effect of poor sleep quality on health. He is public and keynote speaker and teacher at Harvard College. He and his team also organize international award-winning projects such as conferences which attracted 2400+ participants from 30+ countries, 10 Nobel laureates and major leaders in medicine (Plexus Conference), collaborative research projects, charity concerts and other events. He co-founded Med&X Association, a non-profit organization that organizes conferences with Nobel laureates and partners with leading universities and hospitals around the world to help accelerate the development of talented medical students and professionals. Feel free to contact Alen via LinkedIn for any inquiries.